I’m too young for Bowie, and now too young for Prince.

So why do I feel stunned when the icons pass? Why do I feel inclined to tell my friends, write remembrances on Twitter and turn my ears to all the music we can find?

I’ve already attended two Phillies games this year, two more than in most years at this point. There are reasons I don’t go much: I haven’t lived in Philadelphia in a decade; I’m married and have other obligations; and money isn’t just for baseball games. But this year I’ve already gone twice, two weeks ago at Citi Field to watch Vincent Velasquez beat the Mets, and last week at Citizens Bank Park to watch Jeremy Hellickson implode against the Nationals.

And it’s been nice. Despite the chill pushing on me at both games, the warmth of comfort washed over me. I was able to sit back, clutch a beer, maybe a milkshake, and gaze appreciatively at the action on the field. Even if it wasn’t good action. Even if the specter of my team losing by nine runs hovered over my head.

Certainly I can enjoy the activity of baseball, and the environment surrounding the activity, because the stakes aren’t high for the Phillies. Nobody has promised a contending baseball team. Organizational expectations for the big-league club opening this season are considerably low, with focus almost solely on youth development. So I can watch any game knowing not to expect a contending team, but hoping to catch something exciting and interesting to store away for later. That helps.

But I can also have a nice time watching baseball, I think, because I’m seeing life through different prisms these days. I’ve been thinking a lot about my behaviors, my influences, my direction and how I impact others. Therapy certainly helps. Good relationships help, too. I’m different than I was when I wrote here in 2008 and ‘09. Back then, and even in years afterward, tracking all the way until about 2014, I was quick to anger and frustration. I snapped on a dime. The Phillies could trigger it. I’d silence myself, isolate and reject support from others. Back then, especially, a Phillies loss felt like a personal loss.

Thursday, for an hour maybe, Prince’s death felt like a personal loss. It wasn’t. I don’t have any true connection to Prince, and I didn’t really start listening to his music until I reached college. I’ve heard plenty of his music, I own an album or two, but I’m completely unqualified to not only write about Prince, but to also allow his death to affect me in a profound way. To say it does is to admit hubris.

And yet I was stunned. I dialed my wife five times before she finally answered. I tweeted a mess of things while the online community mourned Prince’s sudden passing. And this morning I flocked to the satellite station playing Prince’s music all day, all weekend.

I need whatever connection I can grasp, especially since I feel slightly more broken than those around me. For me, at least, a song can transport me to a unbelievably specific scene. If I hear TLC’s “Diggin’ on You,” I’m suddenly at a classmate’s birthday party, once again rejected by my fifth-grade class, once again crying for being different and misunderstood. If I hear the Style Council’s “You’re the Best Thing,” I’m hiking the Samaria Gorge with my wife, one of the most incredible experiences of my life.

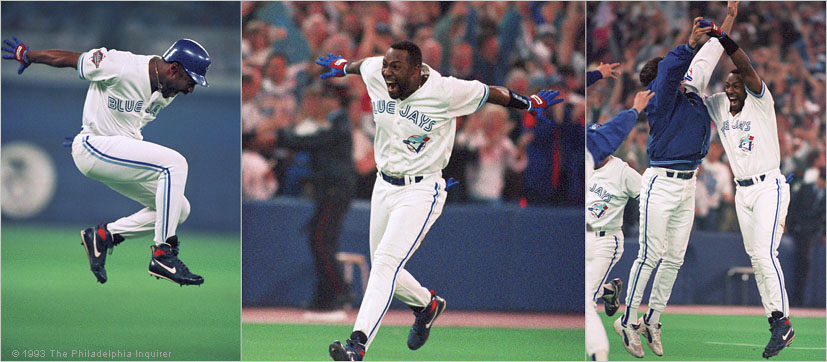

And then there’s baseball. I can tell you where I sat for Terry Mulholland’s no-hitter. I still remember the bunting of Game 3 of the 1993 World Series, proof to me that I actually was at a World Series game. And, of course, I still remember racing to my bed pillows even before Joe Carter stepped to the plate in Game 6. But I also remember sitting at home plate in the 500 Level when Billy McMillon and Mike Lieberthal both swatted grand slams in a win over the Giants. And of course I remember where I was when the Phillies won the World Series in 2008, but I also remember where I was for every other game that postseason. And where I was in 2009, 2010 and 2011.

It’s why it was excruciatingly hard to watch Jimmy Rollins go to the Dodgers, and Cole Hamels go to the Rangers, and Chase Utley go to the Dodgers. It’s why I’ll hang my head the moment Ryan Howard’s career ends in Philadelphia. It’s hard stripping myself of the realization that the past is exactly that, and while we can remember and still be transported to a time and place, nothing will ever take the place of that very present moment.

And that’s why the losses were so personal. Those moments were mine, and at that present there was optimism, more happiness than sadness, more light than darkness. I’ve denied the darkness. I’ve ignored discussing death and illness, sure, but I’ve also ignored paying my bills, visiting the doctor, having difficult conversations and even putting my work out into public. As a published writer I can’t bear to put my words in public, because people may loathe them, spit on them, throw them aside like everything else they came across before. That’s darkness. I’ve denied it as much as possible, and so I’ve distracted myself with everything else: food, alcohol, easy relationships, entertainment and games.

But how dare reality intrude on my light? How dare it step into my optimism and happiness? It’s bad enough I have to go back to work, and I have to have a difficult conversation, and I have to pay my bills and watch my hard-earned work go everywhere else but back to me. How dare reality interrupt my baseball, the finest outlet I have?

I’m learning, though. I have to confront reality, because when I do, I’ve realized that reality isn’t so bad, that it’s simply life; and if I cherish the reality like I cherish everything else that I think isn’t reality, I can succeed in this life. Because then I realize that everything – even the distraction – is reality. It’s all present. Every moment is my present moment.

So maybe baseball is more present than ever. Maybe I’m trying not to project my hopes on a baseball team ultimately designed to entertain fans and make money for owners.

Things still hurt, though. Things can still stun me.

But that’s just being human.

The chorus in Prince’s “The Ladder,” off his 1985 album “Around the World in a Day,” addresses our human journey:

“Everybody’s looking for the ladder. Everybody wants salvation of the soul. The steps you take are no easy road, but the reward is great for those who want to go.”

I’m starting to understand that more. Baseball is a beautiful present thing in my life today. It doesn’t need to spark anger or frustration. It can just be there, with all of the things that have made me who I am, as much as I may still want to retreat to those memories and relive the turbulent thread of growing up.